The Woolcock Institute of Medical Research

Personal reflections on COVID

In January, the Woolcock's Professor Brian Oliver caught COVID. Here he reflects on what it was like, the long-term consequences of the virus, and his own research into COVID and respiratory disease.

Tell us about your own personal experience with COVID

When I look back over the last year, it's amazing how quickly the extraordinary became commonplace. Home quarantine due to being a close contact was an all too frequent experience for me (I endured three periods of quarantine).

In the past two months, COVID exposure notifications via the Service NSW app became commonplace – so much so that I was ignoring them.

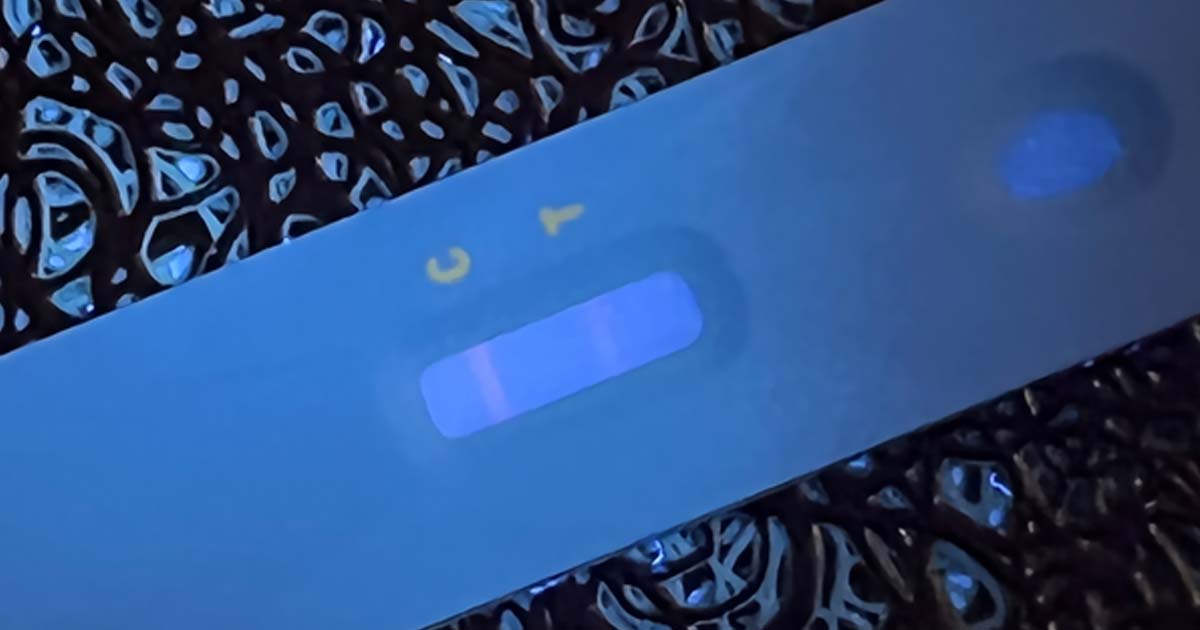

So when I was notified in January 2022 that I was a close contact, I didn’t think anything of it; I had no symptoms whatsoever. But I thought that I would take a rapid antigen test (RAT) at home just in case.

The test was positive. Shock, denial, acceptance, and confusion regarding the public health rules kept me busy for the first 24 hours. Then the symptoms started. I'm fortunate these were very mild, like a bad cold or mild flu.

I was embarrassed at having caught COVID. I had been sensible, and only had minimal contact with other people.

Initially, my embarrassment meant I was reluctant to let people know, but of course I did. Contact tracing is for the most part left to the infected individuals. I decided I needed to approach telling each person in a different way: some by phone, some via SMS, and some by arranging a friend to help them understand what it meant.

Fortunately, I had not passed on the virus to anyone, which has always been one of my greatest fears about catching COVID-19.

On day six, NSW Health sent me my health release certificate for my release back into the world. But should I really go out? Am I a risk to others?

On my first day back at work I consciously kept further away from people, but like in many workplaces, the majority of my colleagues had lived with a person who was COVID positive over the Christmas-New Year period, and they were not anxious about being around me.

I have given some thought as to why my symptoms were so mild. Perhaps it’s because I’m triple vaccinated, perhaps the strain of COVID, perhaps I’m just lucky. Whatever the reason, I'm thankful my symptoms were only mild.

Was it easy to use the RAT?

Strangely, using the RAT kit was one of the more positive experiences of being positive. If you're of a certain age – before health and safety applied to children’s toys – you may have had a home chemistry kit. My RAT was just like one of those old toy kits. Swab like this. Mix with that solution. Add only five drops to the test strip. Wait. And then the best part: see if you're positive using a supplied UV light.

Okay I’m a nerd! But for $10 I was transformed into the younger me playing with my chemistry set once again.

Brian's positive test under UV light

What will the long-term impacts of COVID be?

'Long COVID' is the term given to describe the long-term, and as of yet somewhat undefined, consequences of COVID-19.

There are lots of ways to think about long COVID, but the simplest way for me is to consider what happens during an infection at the cellular level.

Viruses can only replicate inside our cells. They spread by causing the cell to 'explode', releasing lots of progeny viruses to infect other cells. The way the body limits infection is to kill the infected cell.

In a severe COVID infection, the cells in lots of different organs are infected, and the ability of these organs to repair once the infection has subsided is what in my opinion would lead to long-term organ dysfunction, or long COVID. So, for example, this may lead to long-term breathing problems.

Long COVID may also result in changes to a person’s mood, ability to concentrate, or their energy levels. It is not known if this is because of the physiological stress of having COVID, or the result of cells in the brain being infected with COVID-19.

Lots of other respiratory viruses can cause long-term health effects, especially when a severe infection results in a person being admitted to intensive care. So as a medical concept, this is nothing new. However, it will be difficult to predict who will have long COVID. How severe does the infection need to be? Are age and underlying health conditions important?

If I had to guess, I would say that the vast majority of people will not experience long COVID, based on what we know about other viruses.

Tell us about your COVID research

My own COVID research has been a rollercoaster experience. Along with Hima Vedam at Liverpool Hospital, our team has been looking at the spread of COVID in hospitalised patients to understand the risks to healthcare workers.

To do this type of research we have needed hospitalised patients. Initially Australia was for the most part COVID-free, and it was difficult to get the study started.

Unfortunately the delta outbreak occurred, and that sent us scrambling to get final approvals to get the project underway.

So far our data shows that in the confines of specially-adapted hospital wards, the risks of transferring COVID to healthcare workers are very low.

We hope our research will show the sorts of protocols and systems needed to keep frontline workers safe from harm from COVID, and reduce the negative impacts of long COVID.