The Woolcock Institute of Medical Research

COVID and airborne disease – a timely reminder

If the pandemic has taught us anything, it has reinforced the importance of airborne aerosols in the spreading and control of infectious diseases.

This might seem obvious now, but over time airborne transmission had become an extraordinarily political and sometimes controversial idea.

There's a long history to the controversy. For some time in Western medicine, all diseases were thought to be caused by the 'miasma', or bad air. For example, malaria (literally 'bad air') and cholera were, wrongly, thought to be the result of the mysterious miasma.

In the early twentieth century, when it became clear that bad air wasn't the culprit causing all disease, the miasma theory finally fell out of favour.

But, as is so often the case, our reaction became an overreaction. In hospitals, for example, the focus for infection control became handwashing and surface cleaning. Airborne protections such as good ventilation and mask wearing were given less attention.

In our overreaction to the miasma, the importance of airborne transmission got somewhat lost.

What we've learnt from COVID – and have known for some time from our work on tuberculosis (TB) – is that airborne transmission can be key to the spread of some diseases.

What's more, recent data on TB shows how simple, routine breathing is the major factor in disease transmission. A person doesn't need to be coughing or wheezing for TB to spread, though these are of course additional risk factors.

As a result, much of the transmission of TB seems to be caused by people who are asymptomatic – though they aren't coughing, they have active TB and can pass the disease on to others simply by breathing.

We've seen the same thing happening with COVID and other respiratory infections.

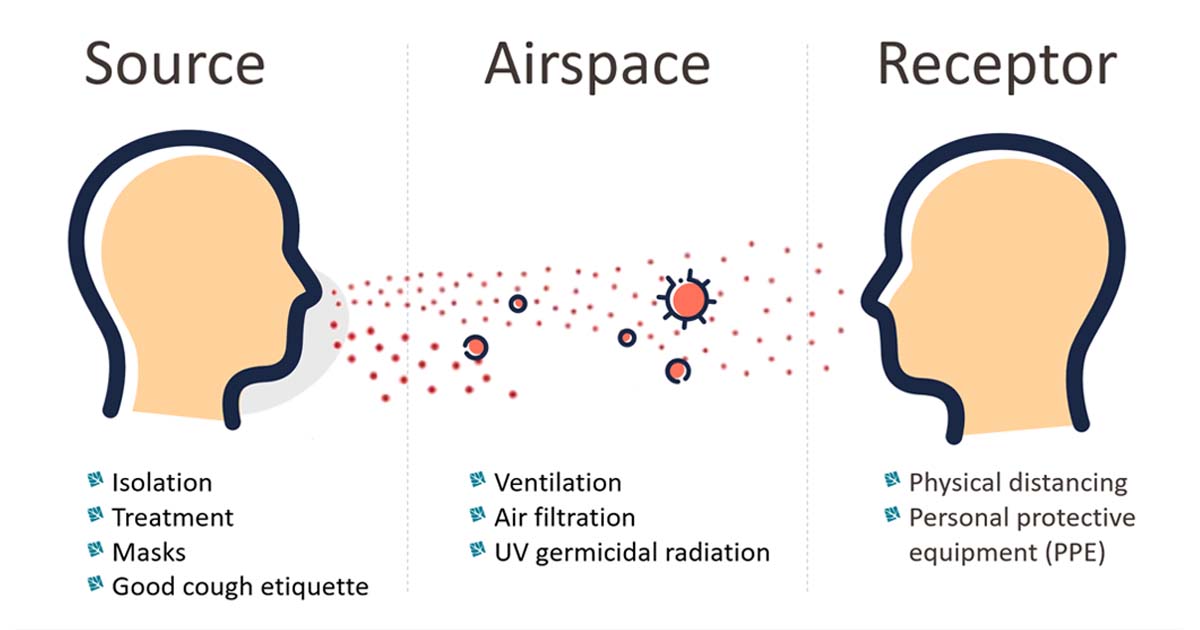

This has huge implications for how we approach disease control for respiratory infections. It means we need to take a layered approach in reducing the hazard of transmission. Control should be targeted to all three parts of the airborne transmission cycle: the source, the receptor, and the airspace between these two.

- The source: Find and isolate the person with the infectious disease. Treat them to reduce infectivity. Make sure people wear masks and practise good cough etiquette.

- The receptor: Ensure people maintain physical distancing and wear personal protective equipment (PPE).

- The airspace: The air between the source and the receptor is also crucial. Indoor spaces need to be well ventilated to disperse disease pathogens. We can ventilate naturally (open doors and windows) or mechanically (with fans). We can also use filtration and germicidal radiation using ultraviolet light.

I believe not enough attention has been paid to the airspace, until now. Part of the problem is that ventilation is not a fixed thing; it relies on many changeable factors, such as the number of people in a space, how many open doors and windows there are, and even weather conditions.

So how can we best track the quality of ventilation? I believe monitoring carbon dioxide (CO2) is a very useful tool as it is a good measure of the adequacy of ventilation in a space.

Both TB and COVID-19 can be 'ended'. We can reach a situation where there's no ongoing or sustained transmission of these diseases. But we need to make sure we are using all the weapons in our arsenal: not just vaccines, but also measures across all three layers of the airborne transmission cycle.

About Guy

Professor Guy Marks is Head of the Respiratory and Environmental Epidemiology Group at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research. Guy's main research interests are in chronic respiratory disease (asthma and COPD), tuberculosis control and the adverse health effects of exposure to air pollution.

Find out more

- Read about some of the COVID-related research we're working on

- Read Open classroom windows key to stopping COVID-19 transmission, ABC News, in which Guy talks about the importance of ventilation in school classrooms for restricting the spread of disease

- Woolcock Vietnam